Every few decades, the pharmaceutical industry discovers a molecule that completely changes the way we live. Insulin did it in the 1920s, penicillin followed in the 1940s, and statins in the 1980s. It’s been a long time coming, but GLP-1-based therapies now appear poised to join that lineage. In a sense, the comparison feels almost unfair: penicillin alone is estimated to have saved around half a billion lives, but outright dismissing weight-loss drugs as monumental misses the point. Sure, Wegovy and Ozempic don’t cure rare, debilitating illnesses, nor do they quell global pandemics, but they touch on something far more common, relatable, and most importantly, human: how millions of people across the globe live, age, and manage their health.

Obesity has spent years in a state of political and commercial limbo. It is a chronic condition that governments have long tried (and ultimately failed) to meaningfully address. It’s also a market that pharmaceutical companies have generally preferred avoiding. For decades, anti-obesity drugs were wildly unreliable, of questionable scientific basis, and burdened by side effects serious enough to overshadow their benefits. Understandably then, most firms wanted nothing to do with it, and those that did venture into the field often came to regret it.

Yet in a matter of 18 months, treatments that once seemed destined for niche use-cases and medicines deemed little more than medical curiosities have rapidly turned into some of the most talked about drugs on earth. Conversations about Ozempic and Wegovy migrated from specialist clinics to cafés, group chats, and office kitchens. This sudden rise to stardom has exposed an apparent contradiction: the same condition that governments spend billions trying to prevent has now become one of the pharmaceutical industry’s most sought-after opportunities. The world seemingly can’t decide whether to cure obesity or capitalize on it.

This tension perfectly frames what happened next: by late 2025, Pfizer and Novo Nordisk, two companies that rarely, if ever, cross paths, had found themselves engaged in the industry’s first public bidding war over a company that had never sold even a single product. Metsera was barely three years old when the two began fighting over it; the young biotech, still in mid-stage trials, only went public in the first quarter of 2025. Within the span of ten months, its valuation had more than tripled, and pharma giants were now willing to pay multiples of that for the firm. The prize for acquirers, of course, was not revenue (there is none) but gaining relevance in a market where demand has been consistently outpacing supply for years.

Pfizer’s path to the bidding table was straightforward. The COVID-19 pandemic briefly turned it into the world’s most profitable pharmaceutical company, yet the inevitable slide downwards from its all-time highs revealed just how dependent it had become on a single set of products. GLP-1 drugs offered something the company no longer had: long-term, repeat-use therapies with global demand. When its internal obesity programs collapsed and with no viable options left to rebuild its pipeline from within, Pfizer had to look outwards. Metsera’s promising metabolic platform was one of the only viable ways left to get back in the race.

Novo Nordisk approached Metsera by starting from the inverse problem. It had already succeeded in building up the modern GLP-1 era that Pfizer planned on joining. Saxenda, Ozempic, and Wegovy had first pioneered, then came to dominate the market, only for Eli Lilly to begin closing the gap between the two at a blisteringly fast pace. The company spent decades operating with little direct competition, yet suddenly, a serious rival was matching it dose for dose, label for label. Once again, Metsera’s platform was one of the only ways left for Novo to take a defensive stance against Lilly and stretch out the lifespan of its obesity care franchise.

What makes this sector, at this particular moment in time, particularly interesting is not just the science behind GLP-1s, but the scale of what’s to follow for the market. We’ve firmly established that obesity treatments are now moving out of specialist clinics and into everyday medical practice, from premium price-points to government-funded channels, from constant supply constraints to worldwide distribution measured in hundreds of millions of doses. The implication being that, at last, obesity has found its ‘miracle drug,’ a milestone that many other markets with huge total addressable market sizes and unbelievable upside potential never see come to fruition. The challenge of drug discovery is over for the space; the bottleneck has now shifted from “Does this work?” to “Can anyone make enough of it?”. In that context, even a young biotech with mid-stage data can look less like a gamble and more like a critical future resource for both Pfizer and Novo.

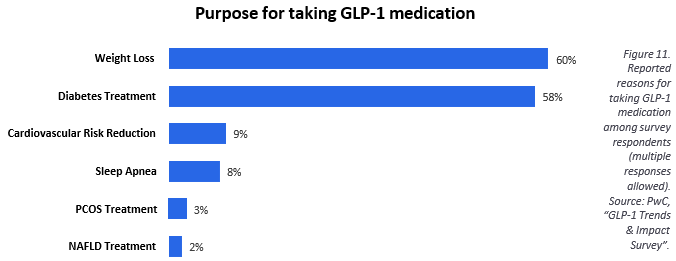

Beneath all of the corporate maneuvering, however, lies the human element turning the market’s wheels; People want these drugs. Not in the abstract, not in the long run, but right now. For many patients, GLP-1 medicines are the first treatments that make long-term weight management feel genuinely possible. They soften the day-to-day demands of a chronic condition that has long been framed as a matter of willpower and demonized by the public at large. In doing so, GLP-1s create expectations that no pharmaceutical company has fully planned for: the anti-obesity market has a permanent, material effect on people’s bodies, lives, and identities.

The bidding war for Metsera perfectly encapsulates all these aspects, minor or major, human and corporate. Metsera was never the largest company, nor the best established, nor even the most advanced. The key element here was timing. Several unrelated clocks: political, regulatory, scientific, cultural, and economic, tirelessly ticking away, all happened to ‘strike twelve’ at the same moment: the one where Metsera was being eyed up as a potential acquisition target.

In it, Pfizer saw a way back into the market it could not afford to stay out of. Novo saw a gap in its defenses just as its closest rival was gaining on them. Everyone saw something different in Metsera, but in the end, it was just what they wanted to see and nothing beyond. However, this opportune timing turned the three-year-old biotech’s acquisition story into insight for the market as a whole: a reminder that, in the pharmaceutical industry, luck and timing sometimes outrun even the best that science has to offer.

Company Overview: Pfizer & Novo Nordisk

Pfizer

Pfizer traces its origins to 1849 as a small Brooklyn producer of chemical and food products. In the early twentieth century, the company gradually built up a strong reputation for reliability and mass manufacturing, becoming one of the first companies to produce penicillin at scale for Allied troops during World War II. This early focus on large-scale production quickly cemented a corporate and business model for Pfizer as a pharmaceutical company of industrial size. By the 1990s, Pfizer’s blockbuster drugs Lipitor and Viagra, along with the acquisitions of Warner-Lambert, Pharmacia, and Wyeth, had turned the firm into one of the world’s largest drug companies. However, this rapid expansion left it vulnerable to looming patent expirations, prompting a restructuring in 2020: Pfizer exited all non-core businesses, such as consumer health and generics, in favour of biotech, vaccines, and precision medicine.

This strategic reorientation proved prescient. Although the COVID-19 global pandemic largely paralysed the pharmaceutical sector, it turned Pfizer into the world’s most profitable pharmaceutical company: In 2022, it was earning $994.80 in revenue per second, almost double that of its nearest competitor, Johnson & Johnson (Tortorice, n.d.). Its partnership with BioNTech rapidly delivered the first approved mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, Comirnaty, naturally meeting unprecedented worldwide demand and generating record profits. However, as the pandemic subsided and vaccine sales collapsed, so did Pfizer’s momentum. Lacking a true growth engine to complement its otherwise mature drug pipeline, and with the obesity space emerging as the next $100bn health market, Pfizer quickly acted. Initially, to compete with rivals Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, Pfizer attempted to formulate their own oral GLP-1 drugs, lotiglipron and later danuglipron, only to halt both trials due to safety and tolerability issues. With its internal R&D efforts finished and millions of dollars wasted, Pfizer has now opted for the quickest route into the market: a direct buy-in through Metsera’s established pipeline.

Novo Nordisk

The origins of Novo Nordisk date back to the 1920s, when two Danish companies, Novo Therapeutisk Laboratorium and Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium, brought insulin production to Europe, inspired by the discoveries of Banting and Best in Canada. They ultimately merged in 1989 to form the modern Novo Nordisk. In contrast to the industrial-scale model embraced by its American counterpart, Pfizer, Novo opted to build itself up slowly, meticulously building its brand around diabetes care and insulin-based therapies throughout much of the twentieth century.

The past decade, however, has witnessed a strategic transformation within the company much like that of Pfizer. Novo’s focus has shifted from blood-sugar control to metabolic regulation and obesity, quickly securing a position as one of the market leaders. With the introduction of liraglutide and later semaglutide, Novo revolutionized metabolic therapy, creating the first GLP-1 analogues capable of both managing diabetes and achieving meaningful weight loss. The result was explosive growth: by 2024, Novo’s obesity-care revenue had risen 56% YoY, largely attributable to global demand for its weekly injectables.

Novo’s goal, therefore, is to defend and extend its leadership in obesity. Acquiring Metsera would have allowed it to broaden its platform with monthly GLP-1 candidates, diversify administration methods, and reduce dependence on a single mechanism, all very important steps when considering the rate at which rival Eli Lilly has been closing the gap.

Ownership and Management

Pfizer, the American company with about 83,000 employees, has a board of directors consisting of 14 members, 13 of whom are independent, chaired since 2019 by CEO Dr Albert Bourla. The combination of experienced leadership and strong board independence, while allowing Pfizer to manage major acquisitions such as that of Metsera, also imposes higher performance standards and a clear and measurable business plan. Institutional investors, with Vanguard (8.9%), State Street (5.2%), and BlackRock (5.1%) among the main shareholders, hold 66.8% of the capital, while the stake held by insiders is minimal (0.1%).

Therefore, being characterized by a broadly held shareholding dominated by index funds, Pfizer places a strong focus on quarterly targets and the sustainability of dividends and share buybacks. Hence, the need for the Metsera deal is to safeguard earnings per share (EPS) in the short term and outline a concrete economic return with growth milestones in realistic timeframes. When carrying out major acquisition deals, Pfizer must aim to strengthen the pipeline without compromising shareholder returns.

Pfizer is aware that the Metsera acquisition would not immediately increase EPS and has predicted overall dilution until 2030. The cash price of $65.60 per share + CVR of $20.65, for a potential value upwards of $10 billion after the last auction bid with Novo, shows that this is a decision taken considering a medium-to-long-term horizon (Pfizer Completes Acquisition of Metsera, Pfizer, 2025). The attractiveness of the acquisition, then, lies in the fact that Metsera represents a real long-term opportunity for Pfizer to compete in the obesity market.

Novo Nordisk’s dual-class ownership structure is anchored by Novo Holdings A/S, a foundation that owns ~28% of the share capital but holds significantly greater voting power through an enhanced-rights class of shares. The remaining equity is widely dispersed across institutional investors (~37%) and a broad base of small shareholders. This system allows the foundation to firmly keep control of the company without requiring a majority stake, which effectively insulates management from short-term market pressure. Consequently, unlike Pfizer, Novo can plan with a longer-term perspective without necessarily having to deliver quarterly results. The company does not have to worry about how an acquisition might affect its balance sheet, but rather if it aligns with its strategy and the leadership it has built up in the few sectors it focuses on. This type of structure also explains Novo’s selective approach to M&A: discipline is rewarded, rapid swings in strategy are not. Any proposed deal must clearly strengthen its market position in diabetes and obesity rather than dilute focus.

Business Overview

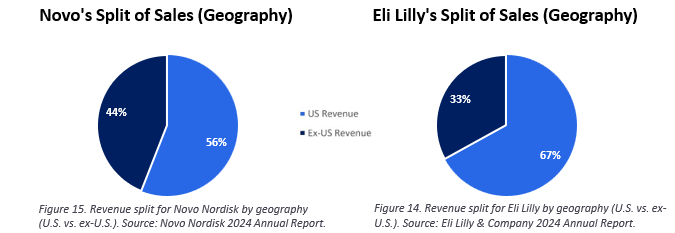

The established profile of Novo Nordisk proved to be a significant advantage as it entered the competition for Metsera. The firm has long defined its identity around metabolic diseases. For FY2024, we note that endocrinology and metabolism constituted approximately 73% of its revenue, with diabetes care alone accounting for over 70%. Specifically, 53% of all revenues come from medication for type 2 diabetes, and 17.5% from Type 1. Anti-obesity medication made up 22% of revenue. It is significant that its main market is the United States, where it generates almost 58% of its revenue: precisely the country where GLP-1 medication is booming.

For Novo, obesity is at the heart of its business. The therapeutic portfolio of Pfizer, by contrast, is broader and more mature: infections (32%), oncology (24.5%), cardiovascular (11.6%), and only 10% in metabolism and endocrinology. Obesity is not yet a pillar. Its all-time leading drugs in terms of revenue generation (Eliquis, Prevnar, Paxlovid, Comirnaty) confirm that. However, Pfizer also heavily relies on the United States (61% of revenue), and is thus well acquainted with the complex world of PBMs/formularies. In the US market, access to medications depends on Pharmacy Benefit Managers that decide which drugs will be covered by insurance, the extent of coverage, and under what conditions (Fein, 2024). Pfizer has long worked with these intermediaries and therefore knows how to ensure that its drugs are included in formularies. In an area like obesity, where coverage of GLP-1s remains uneven and often conditional, this experience is a competitive asset.

Financial Analysis

Pfizer and Novo Nordisk have achieved similar stature while following completely different paths. In FY2024, Pfizer recorded higher revenues ($63.6 billion), which translated to $23.5 billion in EBITDA and $8 billion in net profit, yielding margins of 37% and 12.6%, respectively. Novo, on the other hand, generated less revenue ($42.1 billion), but managed to extract much more value from each dollar: $21.5 billion in EBITDA and $14.6 billion in net profit, with very impressive margins of 51% and 34.8% respectively.

To understand the implications of this, it is paramount to look at the firms’ different structures: Novo focuses on diabetes and obesity therapies, where it can set higher prices and benefit from strong operating leverage, as each additional vial is extremely profitable. Pfizer has a broader and more mature portfolio, which inherently compresses profitability across its product mix. This is how two companies that have a $21 billion difference in sales end up with an almost identical EBITDA: Novo is a machine of efficiency, Pfizer, a machine of scale.

Pfizer channels most free cash flow into dividends, generating $12.7 billion in operating cash flow and $9.8 billion in free cash, yet the firm distributed $9.5 billion in dividends, a figure in excess of its own earnings ($8.0 billion). Indeed, the healthcare giant wants to demonstrate commitment to investors seeking income. By doing so, however, every dollar given in dividends is a dollar not reinvested, forcing Pfizer to take on heavy debt and buy already-mature growth when it needs to move quickly. Novo, on the other hand, generated $10.7 billion in free cash while investing about $7.4 billion to expand its production capacity. It distributes only about 50% of its profits, thus leaving resources to finance both production and the pipeline.

This narrative is reinforced when looking at the firms’ balance sheets. Pfizer has about $46.5 billion in net debt (~1.9x EBITDA) versus $20.5 billion in cash. This level comfortably falls within the typical investment-grade metrics of the pharmaceutical sector and is consistent with credit agencies’ ‘high quality’ ratings. Comparison with peers confirms the picture: Merck 1.3x, Johnson & Johnson 0.7x, and Novo 0.5x. In other words, Pfizer is among the more overleveraged large-cap pharmaceutical companies, but it is by no means in a precarious position. Novo is much lighter, with a Debt/EBITDA ratio of ~0.5 and an impressive interest coverage ratio of 72x. Its liquidity ratios may seem tight on paper, but reality is different: the cash generated from operations comfortably covers all commitments, even with growing investments. Nevertheless, both firms can finance significant moves.

The returns tell the same story with different numbers. Novo’s ROE (81%), ROIC (56%), and net margin (35%) show a model highly focused on high-margin products and an efficient operating structure. This combination allows Novo to generate returns far above the industry average. Pfizer’s ROE (9%) and net margin (13%), on the other hand, reflect its breadth: more products, more complexity, more operations to manage. All of this reduces the company’s average profitability. These are two different models that influence how companies respond to opportunities. Novo invests in areas where it is already a leader and can immediately generate a high return. Pfizer, instead, evaluates whether the investment can truly grow the company and its impact on the consolidated financial profile.

The market valuation also reflects their choices. Pfizer has an EV/EBITDA multiple of about 8 times, a level consistent with a company that still needs to convince the market of the strength of its next growth cycle. Novo’s premium has decreased compared to FY2024, now standing at around 10x on an LTM basis, but it remains higher than Pfizer because the market pays for those high margins and ability to execute. Investors pay for every euro of operating profit because it meets higher expectations on growth, margins, and risk. When the gap between multiples increases, it means expectations about growth and earnings quality are improving. If it decreases, it means the market sees more uncertainty or less defensible margins. This difference influences their behaviour: Novo is rewarded if it remains selective on pricing while investing in production capacity; Pfizer is rewarded if it can ensure credible short-term growth, capable of supporting earnings per share and justifying dividends.

Finally, we can look at the pipelines. Pfizer has 101 candidates spread across various areas (Product Pipeline, Pfizer, 2025). Novo is much more focused on metabolism and cardiometabolic areas, with targeted extensions. Focus does not mean fragility: in Novo’s case, it is a strategy that maximizes returns if GLP-1s remain the driving force. In 2024, Novo generated about $10 billion in revenues from “Obesity” (LTM as of 12/31/24). Pfizer, on the other hand, does not have anti-obesity products after halting its oral GLP-1s for safety reasons: The healthcare giant had to suspend its lotiglipron and danuglipron trials due to tolerability and safety issues.

In the Phase 2b trial, dosing with danuglipron 200 mg BID (4-week dose escalation) resulted in a placebo-subtracted mean weight loss of 12.9% (Buckeridge et al., 2025). However, a patient’s elevated liver enzyme count (a biomarker indicating potential liver damage), which resolved immediately after stopping medication, led the company to terminate the development of Danuglipron definitively in April 2025. The lotiglipron trials were also previously halted due to the presence of the same biomarker; however, many patients had already dropped out of the mid-stage trial due to the drug’s poor gastrointestinal tolerability, which resulted in many cases of severe nausea.

M&A and Growth Strategy

Novo Nordisk: “Defending leadership and expanding the field”

Novo Nordisk has long used M&A to strengthen its metabolic platform rather than to reinvent it. Its push beyond traditional insulin began in 2015 with the acquisitions of Calibrium and MB2, two U.S. biotechs founded by peptide chemist Richard DiMarchi. This marked its formal departure beyond traditional insulin medication. Subsequently, in 2018, Novo acquired the British biotech company Ziylo in an $800 million deal. This transaction secured a platform for developing “glucose-responsive” insulins, designed to make diabetes treatments both safer and more efficient. The key asset, the macrocyclic molecule NNC2215, is engineered to automatically modulate its own activity thanks to a mechanism capable of binding glucose.

The company accelerated this strategy in 2020, acquiring Corvidia Therapeutics for its cardiovascular antibody ziltivekimab and paying $1.8 billion for Emisphere Technologies, acquiring the SNAC technology enabling the oral formulation of semaglutide. In particular, semaglutide has become famous as a “miracle drug,” as it mimics the natural gut hormone GLP-1, enhancing insulin release and suppressing appetite, thus being used for both significant weight loss and as a type 2 diabetes treatment (Ralf Weiskirchen & Lonardo, 2025).

Finally, in 2023, the $1.08 billion acquisition of Inversago Pharma, a company developing next-generation CB1 antagonists designed to act peripherally and overcome the safety limitations of older central CB1 molecules, further broadening Novo’s obesity portfolio. By the time Metsera emerged as a target in 2025, Novo’s logic was consistent: a monthly GLP-1 and a differentiated amylin analogue would diversify dosing formats and reinforce its leadership as Eli Lilly closed in. This is the context in which Metsera was deemed an attractive acquisition by Novo Nordisk, thus placing the firm directly in competition with Pfizer.

Pfizer: “Buy to reinvent itself”

Throughout its history, Pfizer has often relied on M&A to boost growth and strengthen its pipeline. The significant acquisitions of Warner-Lambert (2000), Pharmacia (2003), and Wyeth (2009) were instrumental in consolidating blockbuster drugs like Lipitor and helping the firm cushion the impact of patent cliffs. Today, the company faces renewed urgency as patents for key assets, including Eliquis and Ibrance, are set to expire between 2026 and 2028, placing an estimated $17 billion to $18 billion in revenue at risk (Hargreaves, 2024).

In addition, Pfizer can no longer rely on pandemic-era revenues. The enormous profits (over $90 billion) accumulated through 2022 from the COVID-19 vaccine and antiviral allowed the company to make targeted acquisitions: Biohaven ($11.6 billion), Arena ($6.7 billion), Global Blood Therapeutics ($5.4 billion), and Seagen in 2023 ($43 billion), which was a particularly significant purchase for the firm. In fact, Pfizer’s largest recent purchase added four approved anticancer drugs (with nearly $2 billion in sales in 2022) to Pfizer’s portfolio, ensuring strong long-term growth. Seagen’s pipeline is expected to significantly boost Pfizer’s revenues in the coming years, mitigating the impact of patent expirations on its older drugs.

Company Overview: Metsera

Metsera is a clinical-stage biotech built around a clear engineering problem: pushing obesity drugs into a next generation of convenient, affordable, and safe treatment options. Founded in 2022 by Population Health Partners and ARCH Venture Partners, the company went public on Nasdaq just three years later at an initial $2.7 billion valuation. Within only 10 months, its market value had ballooned to nearly $7 billion, becoming the youngest biotech to achieve this valuation milestone before entering Phase 3 trials. Metsera’s diverse portfolio of promising candidates, dosing strategy, and early trial signals were enough to draw the attention of two companies that rarely compete head-to-head: Pfizer and Novo Nordisk. By November 2025, their parallel interest had escalated into a public bidding war, with Pfizer ultimately acquiring Metsera and slotting it into its Internal Medicine portfolio.

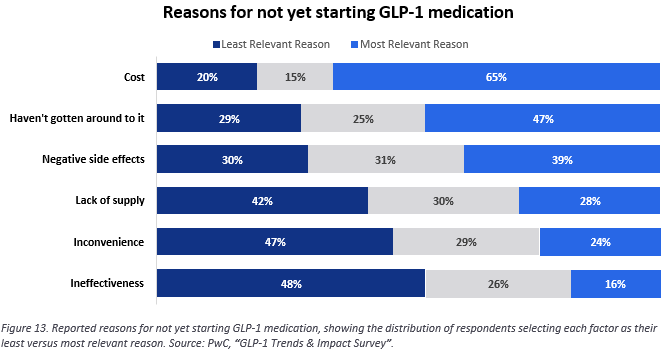

Part of the company’s appeal is timing. GLP-1 drugs have pushed obesity treatment into mainstream medicine faster than anyone expected, yet access remains uneven and often conditional. More than 19 million Americans lack coverage for GLP-1 receptors, and current therapies still require frequent dosing. Amidst this surge of demand, the limitations of current generation therapies have become clear: weekly injections, up-titrating, and oftentimes severe side-effect profiles make adoption difficult for patients outside specialty care. Metsera positions itself just beyond this bottleneck; its programs target multiple hormonal pathways and, crucially, are designed for once-monthly dosing rather than today’s weekly regimens.

Long-acting dosing serves both a clinical and commercial purpose: it mirrors the body’s natural metabolic rhythms, meaning side effects are far easier to manage given that exposure to the drug is steady rather than spiking week to week. It also lowers the friction for primary-care adoption, where physicians often favor treatments that demand minimal monitoring and fit easily into routine prescribing. A monthly injection demands less onboarding, less side-effect monitoring, and fewer follow-up calls. For the patient, these key quality-of-life features will curb early discontinuation and broaden uptake far beyond today’s base of ‘early- adopters.’

Metsera’s lead candidate, MET-097i, is the clearest example of how the company has translated its theoretical aims into measurable clinical progress. In two mid-stage clinical trials, participants lost up to 14.1% of their body weight within 28 weeks, with no signs of plateauing. Analysts expect the obesity drug market to continue expanding as treatment shifts towards long-term therapy. With more than a billion people classified as obese and another two billion overweight, the market demand is massive, and the stakes are high. The growth of the anti- obesity market has serious implications for a broad array of related medical issues: sustained weight reduction can reduce the risk of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and several forms of cancer. The long-term nature of treatment also means that, for companies in the space, the obesity market could potentially become a durable service line.

Following an agreement between the US government and market-leading companies in the global obesity market to reduce the prices of GLP-1 weight loss drugs, Goldman Sachs believes that this can be interpreted as a strategic “price-to-volume” deal. Starting from 2026, patients from both Medicare and Medicaid will be able to obtain GLP-1 drugs at significantly reduced prices. This implies a decline in realized unit price; however, government coverage will expand access and likely increase sales volumes. The overall revenue effect will therefore depend on whether volume offsets the per-unit price reduction, aligning with Goldman Sachs’ interpretation. It is important to note that the increase in sales will not only eventually offset the impact of price declines but also increase the patients’ compliance and enhance price stability. Since a drug’s price is one of the key factors that may lead to medication discontinuation, by enhancing price stability, the sector could avoid more severe price wars between competitors.

While Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk have already finalized the government agreement to price their obesity drugs through Medicare and Medicaid, Metsera has not yet entered into such agreements since it is a pre-revenue clinical-stage company, currently offering no drugs on the open market. However, Pfizer’s position within the U.S. political landscape and deep understanding of the pharmaceutical sector heavily imply that Metsera’s pipeline drugs will also enter the Medicare and Medicaid coverage programs, possibly within only months of their initial launch to market.

Ownership and Management

Metsera’s board has been unusually hands-on for a company this young. Its strategy has revolved around securing long-term partnerships to bring its pipeline to market. Much of this preference for long-term value is found in the Board’s hands-on role in steering strategic direction, evaluating potential partners, and assessing risk by enforcing a considerable amount of expertise both scientifically and in fields such as consulting, venture capital, and investment banking. For a pre-revenue company advancing costly metabolic programs, governance is one of the few tools that can meaningfully reduce the execution risk typical of most biotech startups.

The center of attention is Clive Meanwell, who founded Metsera in 2022 and now serves as its Executive Chairman. Meanwell has spent years working in both drug development and biotech investing, and under his strategic direction, Metsera was able to make a series of decisions that would come to define the company’s future success. The first of these was the $77.2 million acquisition of Zihipp in 2023, which gave Metsera access to a library of more than 20,000 gut-hormone peptides. The second was assembling a board of highly experienced and medically capable members, with particularly deep knowledge of the metabolic medicine sector. Lastly, Meanwell attracted a large amount of elite institutional investors such as Mubadala, SoftBank, and ARCH Venture Partners, an effort that undoubtedly helped Metsera raise close to $300 million in its series A round, and positioned it as a credible entrant in a market dominated by industry giants like Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly.

Day-to-day execution has fallen to Christopher Bernard, Metsera’s CEO since 2024. Bernard’s background in commercial strategy and operations shaped the company’s transition from a quiet venture-stage project to a clinically advancing platform with multiple injectable and oral programs. Under his oversight, Metsera built out manufacturing readiness early, pushed MET-097i toward late-stage development, and prepared the company for the public markets. During the takeover contest, Bernard also served as a key strategist, helping frame Metsera not just as a promising biotech but as a viable acquisition target for the two most powerful players in obesity care. While the bidding war for the biotech puts an imminent end to the listing of Metsera’s stock on the NASDAQ, the previous top shareholders for the obesity company included:

BSMAC firmly believes that Metsera’s top shareholders list heavily implies a company of immense quality. Such a concentrated group of high-profile, institutional backers signals early confidence in both the company’s science and its governance. These factors, combined with a pipeline that looks differentiated even in a highly competitive market, has helped Metsera build up a reputation as a serious contender in obesity therapeutics long before it even reached late-stage trials, positioning the firm near the top of the obesity market.

Pipeline and Differences Between Drugs

The company’s pipeline centers on two candidates: MET-097i, a once-monthly GLP-1 injectable, and MET-233i, an injectable amylin analogue designed both as a monotherapy and as a co-formulated combination therapy with MET-097i in solution. According to David Risinger, analyst at Leerink Partners, “Metsera’s experimental obesity drugs, MET-097i (…), and MET-233i (…) are projected to reach $5 billion in combined peak sales” (Jaiswal et al., 2025). Risinger’s projection is reflective of the current market dynamics more so than the quality of the candidates. Obesity is a vast therapeutic category with over one billion potential patients, but adoption of GLP-1 drugs is still at an early stage. An estimated 2–3% of the eligible U.S. patient population uses them, and uptake in most other countries sits closer to 1% (The Exponential Growth of Obesity Drugs, Morgan Stanley, 2025). The room to grow is enormous, and the steepest part of the adoption curve is likely still ahead as insurance coverage expands and primary care prescribing becomes more routine.

Metsera began substantiating its dosing ambitions in September 2025, when it released mid-stage data for MET- 097i, its lead GLP-1 receptor agonist. The results for two phase 2b trials, VESPER-1 (consistent dosing between 0.4 mg and 1.2 mg) and VESPER-3 (one- or two-step titration up to 1.2 mg) showed a mean placebo-subtracted weight loss of up to 14.1% after 28 weeks of dosing. An exploratory analysis of the VESPER-1 study extension at 36 weeks demonstrated substantial continued weight loss. VESPER-1 had a 2.9% total study discontinuation, and in the VESPER-3 trial arm that titrated from 0.4 mg to 1.2 mg over 12 weeks, there was minimal diarrhea signal, a 13% risk difference from placebo for nausea, and 11% for vomiting. There are class-leading tolerability and efficacy results, and based on the positive topline data, Metsera has officially confirmed a global Phase 3 program beginning in late 2025 (Metsera Reports Positive Phase 2b Results for First- and Best-In-Class Ultra-Long Acting GLP-1 RA Candidate MET-097i, Enabling Rapid Transition into Phase 3, 2025).

Metsera also advanced MET-233i, its amylin analogue designed for combination use. Phase 1 data showed 8.4% placebo-adjusted weight loss by Day 36, a half-life of roughly 19 days, and a tolerability profile close to placebo. For an amylin monotherapy, those numbers were notable: amylin analogues historically struggle with gastrointestinal tolerability and have limited early weight loss gains. According to Chief Medical Officer Steve Marso, the company “observed five-week weight loss comparable to leading GLP-1s” and identified “efficacious starting doses with placebo-like tolerability.”

However, MET-233i is not meant to compete with GLP-1 agonists head-to-head. Although it is being developed as a monotherapy, its primary draw lies within Metsera’s proposed combination therapy: MET-097i acts as the long-acting GLP-1 backbone, regulating appetite, and the amylin analogue slows gastric emptying, promotes the feeling of satiety and lightens glycemic swings. The end-goal for the therapy is emulating the body’s natural hormonal pattern rather than just amplifying GLP-1 signalling.

Benchmarking will help us illustrate the gap that Metsera is trying to close. For example, semaglutide (Wegovy) delivers a 14.9% mean weight loss by week 68 at a 2.4 mg weekly dose. Tirzepatide (Zepbound), a dual GIP/GLP- 1 agonist, achieved a mean weight reduction of up to 20.9% at 72 weeks. Against these already marketed drugs, MET-097i’s 14.1% placebo-subtracted effect at 28 weeks is competitive on trajectory, particularly given that Metsera’s program is built for monthly administration rather than weekly injection.

The comparison becomes sharper when considering the “next-generation” candidates, multi-agonists designed to push efficacy far beyond GLP-1 alone. Eli Lilly’s retatrutide, a triple GIP/GLP-1/glucagon agonist, achieved 24% mean weight loss at 48 weeks in Phase 2. On raw efficacy, MET-097i cannot match those numbers. But retatrutide’s mechanism introduces trade-offs: glucagon agonism can stress the liver, elevate heart rate, and increase myocardial workload. So, while retatrutide may set the standard for what’s currently possible in the market, MET-097i is more of a conservative but scalable and combinable GLP-1 backbone, often used in combination with MET-233i.

This technical nuance is central to Metsera’s strategy. The company isn’t trying to leapfrog the highest-efficacy drug on the market. It is trying to build a scalable and combinable GLP-1 backbone, easy to combine, dose, and manage. In that context, MET-097i’s role is not to outgun retatrutide in sheer numbers, but to fill in the missing gap in the obesity market that is also, in a sense, the ‘elephant in the room:’ a long-term treatment option that clinicians will prescribe and patients will take for years rather than months. These medical distinctions are not only relevant from a clinical perspective but also help explain why Metsera’s assets became so strategically valuable for acquirers like Pfizer and Novo Nordisk.

Financial Analysis

From a financial perspective, Metsera portrays the standard profile of a high-growth, pre-revenue biotech attempting to scale into late-stage development before investor funding runs dry. As of Q1 2025, the company held $583.3 million in cash and equivalents, enough to run mid-stage trials comfortably, but nowhere near what it would take to carry an obesity franchise through Phase 3. The cost curve shows why. R&D spending jumped from $15.6 million in 2023 to $107.5 million in 2024, driven by the expansion of the MET-097i and MET-233i programs and by the clinical trials themselves, which are unusually expensive due to their long dosing windows, heavy monitoring, and high patient numbers. Operating losses rose sevenfold in 2024 and another 70% on a LTM basis, pushing total operating expenses to $224.8 million last year.

On paper, that gives Metsera roughly 3.5 years of runway at a burn rate of $25 million a month. In practice, this figure is misleading; Phase 3 trials in obesity routinely cost over $500 million, and once recruitment begins, cash burn accelerates sharply. The company’s current liquidity was never going to bridge that gap on its own. Metsera was heading toward a major capital raise; an acquisition simply arrived first.

This is the opening Pfizer stepped into. With its own obesity programs halted and the market moving quickly, Pfizer needed a way back in, and Metsera offered exactly that: a late-stage-ready GLP-1 backbone, a combination-ready amylin analogue, and a pipeline built around monthly dosing. Metsera’s angle fits cleanly with Pfizer’s strengths in primary-care scale and chronic-disease management. MET-097i’s trial data supports the case, with only two out of 239 participants dropping out due to adverse events in VESPER-1, and a similarly high retention rate in VESPER-3.

Financially, Metsera was also an unusually clean target. The company carried no debt, minimal long-term liabilities, and a capital structure untouched by royalty deals or complex financing instruments. For Pfizer, this meant a straightforward takeover: no refinancing, no restructuring, and no legacy obligations to unwind. A transaction that might have taken months elsewhere moved quickly here, not just because the science behind it was solid, a fact that we’ve already established, but also balance sheet was thanks in part due to the excellent strategic direction of Metsera’s board.

These factors are all perfectly aligned to position Metsera as a strong acquisition target for Pfizer and Novo. Though the hasty and complex nature of the deal may present itself as a ‘bet’ of sorts, realistically, a Metsera buyout was inevitable, a game of waiting for a firm with the capital and incentive to act. Pfizer simply got there first.

M&A and Growth Strategy

Metsera’s appeal wasn’t limited to its science or its balance sheet. The company also arrived at the bidding table with a track record of unusually sharp deal-making for a biotech still in its infancy. One of the most influential moves came in mid-2024, when Metsera used part of its $290 million Series A funding to acquire Zihipp, a small UK-based biotech spun out of Imperial College London in 2012. Zihipp brought with it one of the world’s largest libraries of gut-hormone peptides, comprising more than 20,000 variants derived from nutrient-stimulated pathways, along with the scientific infrastructure to screen and refine them.

This acquisition changed Metsera’s trajectory. Instead of being another GLP-1 start-up hoping to compete on dosing convenience alone, the company suddenly had access to a broader palette of metabolic mechanisms, allowing it to mix and match the peptides from Zihipp’s library to develop combination therapies. MET-097i emerged directly from this expanded toolkit, as did Metsera’s strategy to design multi-hormone combinations that mimic the body’s native satiety circuits rather than rely on a single lever. In fact, the Zihipp drug candidate that became MET-097i was invented by Professor Steve Bloom, Metsera’s vice-president of R&D, who originally discovered that GLP-1 affects appetite in 1996 while working as a researcher at Imperial University.

Around the same time, Metsera signed a licensing agreement with D&D Pharmatech, a Korean biotech known for its work on oral peptide delivery systems. The deal gave Metsera access to technology aimed at turning injectables into orally dosed candidates, a capability that has become increasingly valuable as companies race to reduce the burden of weekly injections. With D&D’s platform, Metsera gained not only a scientific hedge but also a practical path toward expanding its portfolio into oral GLP-1 formulations, an area where demand is already outpacing supply.

This is ultimately why the acquisition of Zihipp plays such a key role in Metsera’s story. It provided the raw materials for Metsera’s differentiated programs, compressed the timeline to mid-stage development, and prevented the company from being dismissed as “just another GLP-1 company.” It is safe to say that, despite its small size, the few well-placed strategic acquisitions Metsera has undertaken have played a key role in turning the firm to such a compelling big pharma target. Building a unique, high-value asset base would not have been possible without the help of the London-based biotech.

Valuation

Premise

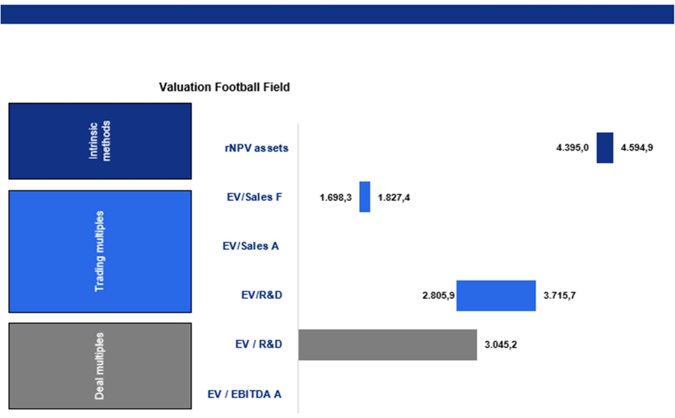

Metsera is an early-stage biopharmaceutical company with an operational life of three years. Due to its pre-revenue status, limited operational structure, and focus on a small number of main assets, traditional valuation metrics such as EV/EBITDA or EV/SALES Actual ratios are not applicable. For our valuation analysis, we used three main approaches: the rNPV model, company comparables, and transaction comparables. A summary of the results is presented in the football field chart below.

rNPV

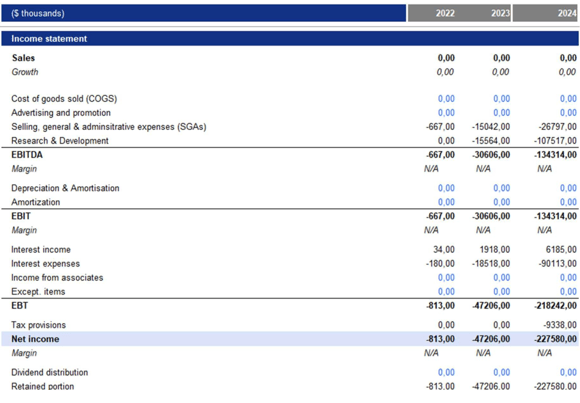

The rNPV analysis decision was taken, primarily looking at the restatement of Metsera’s financial statements for the years 2022, 2023, and 2024. The restatements, detailed below, reveal that Metsera lacks a clear structure. Over the past years, the primary focus has been on the costs associated with drug development.

Since Metsera is still in the early stages of development, with its cost structure primarily composed of R&D activities, the company’s intrinsic value relies entirely on the expected future cash flows from its assets. Additionally, Pfizer is primarily interested in Metsera’s assets, regardless of its overall structure. For these reasons, a risk-adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV) analysis is more suitable for evaluating Metsera’s intrinsic value.

rNPV is therefore the most appropriate valuation approach, as it incorporates the long development timeline of pharmaceuticals, probability-adjusted clinical success rates, the economics of commercialization, and the absence of meaningful operating leverage or debt.

Revenues

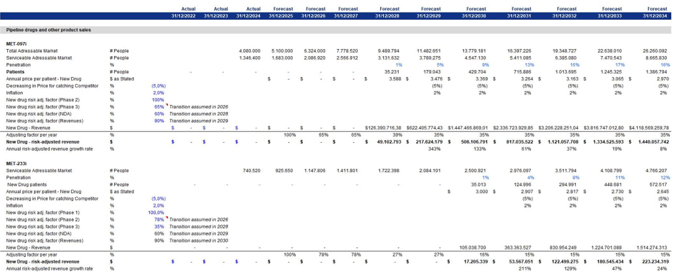

The rNPV model starts with several assumptions to forecast potential revenues over the next 10 years, from 2025 to 2034. We evaluate two primary clinical drugs being developed by Metsera, which are expected to reach the U.S. market: MET-097i and MET-233i.

For modeling revenues, we used a top-down approach to the US obesity market. We estimated the revenues separately for the two assets, calculating them as the annual price multiplied by the number of patients.

First, we estimated the number of patients for each year starting from the current U.S. population of 340 million people (according to Statista). Next, we calculated the total addressable market by taking into account that approximately 40% of adults in the U.S. are considered obese (according to market analysis) and then applying this percentage to the 3% of eligible patients currently undergoing treatment (according to FairHealth). From the total addressable market, we estimated the serviceable addressable market by considering the cumulative market shares that Metsera can reach and the share of the market that chooses to use GLP-1. We anticipate that around 55% of this market will choose to use GLP-1 medications.

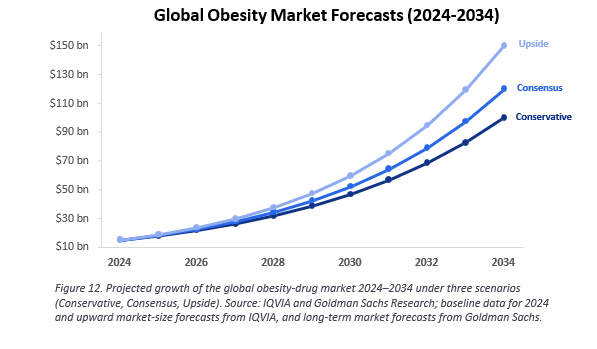

Assuming improvements in access, increased competition, pricing pressures, and enhanced scalability, we project that within 5 to 7 years, Metsera could reach approximately 50-60% of the market, with a market penetration upwards of 20% at peak sales. Finally, we estimated that the serviceable market for GLP-1-based obesity treatments will grow by approximately 25% annually, with a gradual decline of 1% each year. This aligns with projections from IQVIA and Goldman Sachs, which forecast a high double-digit annual expansion in the GLP-1 user base as access improves and manufacturing capacity increases. Real-world claims data from FAIR Health indicate that GLP-1 adoption has risen from 0.3% in 2019 to over 2.05% in 2024 among eligible obese adults. This supports our assumption of an initial penetration rate of around 1%, eventually reaching a long-term ceiling of about 15%.

After estimating the annual number of patients, we estimate an annual net price of approximately $3,000 per patient for MET-097i and MET-233i. This estimate is based on benchmarking against the net prices of currently marketed GLP-1 obesity drugs. Peer-reviewed evidence indicates that manufacturer discounts for obesity- indicated GLP-1s average around 41%. This results in net monthly prices ranging from $717 to $761, which translates to approximately $8,600 to $9,100 per year after accounting for mandatory rebates to Medicaid, 340B, Medicare Part D, and commercial payers. Market reports from IQVIA, Goldman Sachs, and FAIR Health emphasize strong competition and payer-driven pressures on GLP-1 pricing. As the market shifts toward a volume-based model, net prices will likely continue to decrease. Given that Pfizer is expected to implement a pricing strategy similar to that of Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, along with increasing public coverage and rebate depth, we project a long-term net realized price closer to $3,000 per year. This reflects a discount of about 60% compared to current list prices. To reflect the increased competition expected through 2030, we incorporate a -3% annual real (inflation-adjusted) price decrease. This adjustment is consistent with observed net-price erosion trends in the GLP-1 category due to broad payer coverage and expanded manufacturer rebates.

Following the rNPV approach, we estimated the adjustment factor for the drugs expected to be released in the coming years. The clinical success probabilities for each stage of development were derived from the benchmark progression rates detailed in Deloitte’s reports titled ‘Measuring the Return from Pharmaceutical Innovation’. These reports provide industry-standard estimates for the transitions between Phase 1, Phase 2, Phase 3, and regulatory approval. The Deloitte benchmarks are commonly utilized in rNPV and biotech valuation models and correspond with long-term historical averages reported throughout the pharmaceutical industry. Specifically, we estimated that:

1.) MET-097i is expected to reach Phase 3 in 2026, with a 65% probability. Once it reaches Phase 3, there will be a 60% chance of successfully passing this phase by 2028. Finally, there is a 90% likelihood that it will generate revenue by 2029. MET-233i is expected to reach phase 2 in 2026 with a probability of 78%. It will then have a 35% chance of passing phase 2 in 2028, and the same probability for the following phases will be applied as was used for MET-097i.

2.) The final revenues are so derived separately for each drug by multiplying the number of patients by the annual price per patient and discounting for the cumulative probability of success.

Costs

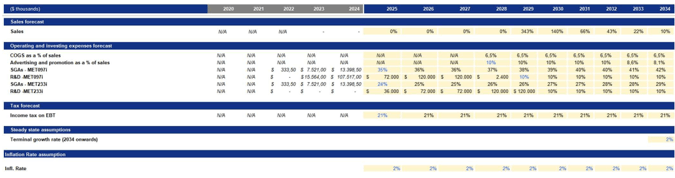

After obtaining the revenue data for 2025-2035, we estimated the costs for the following years, still divided between the two Metsera drugs. The estimates of these costs are outlined below.

Specifically, we estimated four main components of costs: COGS, advertising and promotion as percentages of sales, along with SG&A and R&D, which are assessed separately for each drug.

COGS was estimated as a percentage of sales based on the median cost structure of Metsera’s most reliable commercial-stage peers, specifically Madrigal Pharmaceuticals and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals. These companies serve as the closest analogues available, as they have recently moved from the pre-revenue research and development stage to commercial operations.

Advertising and promotion expenses were estimated following industry best practices for launching new drugs. In the year of launch, we project spending to be approximately 10% of sales. This reflects the typical brand-building investment required for first-in-class or best-in-class therapies entering a highly competitive market, such as GLP-1–based obesity treatments. This level of promotional intensity aligns with disclosures from commercial-stage peers and benchmarks reported by IQVIA and EvaluatePharma for specialty-care drug launches, where early promotional spending generally ranges from 8% to 12% of product revenues. After the initial launch period, we expect advertising and promotion expenses to grow at rates consistent with inflation. This reflects the industry trend where marketing intensity decreases once brand awareness, formulary access, and prescriber adoption stabilize.

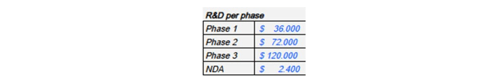

The research and development (R&D) costs for the two drugs were estimated separately for each drug based on industry costs for each phase, utilizing data from Deloitte’s reports titled “Measuring the Return from Pharmaceutical Innovation.” After their release, an estimated 10% cost of sales for innovation was applied.

SG&A (Selling, General, and Administrative) expenses were estimated based on industry-standard benchmarks for commercial-stage biotech companies. At launch, we anticipate SG&A spending to be between $40 million and $60 million. This estimate aligns with disclosures from similar companies that have transitioned from research and development to commercial operations, including Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, and Amarin. This initial level of SG&A reflects the necessary investments in corporate infrastructure required at launch. After the first year following the launch, we expect SG&A expenses to grow at a rate consistent with inflation, which is in line with peers.

Then, we estimated the tax implications using the marginal corporate tax rate in the United States, currently set at 21%. This rate reflects the federal government’s taxation policy aimed at corporate profits. Furthermore, we estimated the projected inflation rate for the upcoming years, which is targeted at 2.1%, according to data from the Federal Reserve.

Total costs were calculated based on the assumptions stated above for each drug and were discounted using the same discount factor of revenues for that drug and its corresponding year.

Output

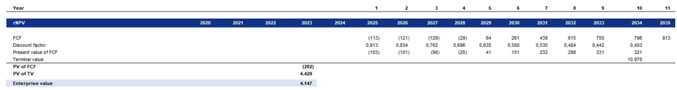

Subsequently, we derived the free cash flow (FCF) for the next ten years:

Discounted Valuation

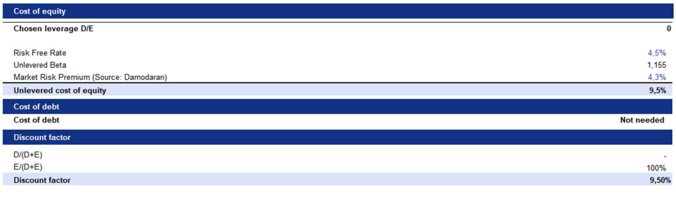

Following the rNPV approach, we discounted Metsera’s probability-adjusted free cash flows (FCFs) using an unlevered discount rate. This rate was derived by applying the company’s unlevered beta to the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). As an early-stage biotechnology company with no commercial revenues, no cash-flow-generating assets, and no plans to support operations through financial leverage, Metsera is effectively financed entirely through equity and research and development (R&D) capital, which is typical for pre-commercial biotech firms. Consequently, debt does not significantly impact Metsera’s capital structure, making a traditional Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) calculation inappropriate. Instead, we use the unlevered cost of equity as the project-level discount rate. This methodology aligns with industry standards in rNPV valuations, where clinical and regulatory risks are included through probability weighting of cash flows, while the discount rate accounts solely for systematic risk.

We then assumed a perpetual growth rate in line with the long-term U.S. inflation rate of 2.1%. This reflects our expectation that once Metsera’s lead products reach steady commercial maturity, their long-term revenue and cash flow growth will align with overall economic inflation, rather than continuing to grow at the accelerated rates observed during early-stage development.

By using this perpetual growth rate alongside the unlevered discount rate, we were able to calculate a terminal value at the end of the forecast period. We then discounted this terminal value back to present value to determine Metsera’s Enterprise Value.

Our valuation based on the rNPV indicates an Enterprise Value of $4.147 billion. When we adjust for Metsera’s net cash position of $344 million, the Equity Value is approximately $4.491 billion. With a fully diluted share count of 105 million shares, this translates to an implied intrinsic value of €42.646 per share. In comparison, Pfizer’s announced acquisition price of $10 billion implies a premium of around 141% over our standalone equity valuation. This premium is slightly lower than FactSet’s (158%), indicating that our model shows a marginally a higher EV of about 7%.

Trading Multiples

For the market multiples valuation, we selected five primary competitors of Metsera that operate within the same industry and are at a similar stage of development. The peer group used in our trading multiples analysis consists of Altimmune, Viking Therapeutics, Zealand Pharma, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, and Terns Pharmaceuticals. These companies were chosen because they are the most relevant publicly traded benchmarks for Metsera across three critical dimensions: therapeutic focus, stage of development, and business model similarity typical of pre-commercial or early-commercial metabolic and obesity biotech companies. All five peers operate in the metabolic or obesity-related therapeutic space, developing GLP-1 agonists, GIP agonists, amylin analogues or therapies for liver and metabolic diseases that directly overlap with Metsera’s target markets.

Viking and Altimmune are among the closest comparables, as both are developing next-generation incretin-based or dual-agonist obesity drugs and have gained prominence in the GLP-1 competitive landscape. The peer companies are at a similar clinical stage, ranging from mid-Phase 2 to early commercial launch. This is crucial because the valuation drivers for metabolic biotechs change significantly once they reach commercial scale. Madrigal and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, although slightly ahead of Metsera, provide important benchmarks for post-approval cost structures and the transition from R&D to sales.

Furthermore, all peers have a biotech model, where enterprise value is driven almost entirely by pipeline expectations. None of these companies has diversified product portfolios outside of metabolism or obesity, which ensures that their valuation multiples, particularly EV/R&D and forward EV/Sales, are highly sensitive to clinical progress and market expectations.

For each peer, we calculated the Enterprise Value by adding net debt to market capitalization. We then related this EV to two key operating metrics: current research and development (R&D) spending and forward sales, where data was available. Since most of these companies are still in, or have only recently exited, the pre-revenue phase, traditional metrics like EV/EBITDA or P/E are not meaningful. Instead, the market primarily values these companies based on EV/R&D, and for those further along in their development, forward EV/Sales.

Based on the analysis, the peer group has an average EV/R&D multiple of 29.1x and a median of 32.6x. In contrast, Metsera has an implied EV/R&D multiple of 72.2x, representing an enterprise value of approximately $7.8 billion with $107.5 million allocated for R&D. This indicates that Metsera is valued at more than twice the intensity of R&D spending compared to its peers. If we apply the average and median peer EV/R&D multiples to

From Metsera’s 2024 R&D expenditure of $107.5 million, we derive implied enterprise values of $3.1 billion and $3.5 billion, respectively. To further validate these figures, we also assessed an EV/Sales forward multiple using external benchmarks for specialty and obesity drugs, sourced from the Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions & Alliances, Nelson Advisors, and Finerra. These sources indicate an average EV/Sales (5-year forward) multiple of 7.4x. By multiplying this benchmark by Metsera’s projected 5-year forward revenues of $217.6 million, we arrive at a lower implied enterprise value of approximately $1.6 billion.

Overall, the trading multiples analysis indicates that Metsera’s fair value range is approximately $1.6 to $3.5 billion based on public market comparables. This is significantly lower than the current implied enterprise value of $7.8 billion, as well as Pfizer’s acquisition price of $10 billion. This discrepancy is expected, as public markets typically discount early-stage, pre-revenue biotechs due to factors such as clinical risk, lack of cash flows, financing uncertainty, and high expectations of dilution. As a result, metrics like EV/R&D tend to be lower. Furthermore, trading multiples do not account for strategic value elements like commercialization synergies, manufacturing scale, portfolio fit, and competitive positioning against companies like Novo and Lilly, factors that a buyer like Pfizer takes into full consideration. Consequently, public market comparables yield a lower EV range of $1.6 to $3.5 billion compared to our standalone intrinsic valuation of $5.5 to $6.0 billion and Pfizer’s strategic acquisition price of approximately $10 billion.

Deal Multiples

For the precedent transaction analysis, we focused on recent M&A deals within the same therapeutic and development space as Metsera. The sample includes the following five acquisitions of early-stage or early-commercial metabolic companies:

All the transactions involved a 100% stake and featured very high takeover premiums, typically exceeding 100%. For each deal, we calculated the Enterprise Value by adjusting the equity value for net debt. We then related the EV to the target’s actual research and development spending at the time of the announcement, as well as to sales and EBITDA when applicable. Since nearly all targets were still unprofitable and generated little to no revenue at the time of acquisition, the EV/EBITDA and EV/Sales ratios are either not meaningful or highly distorted. Therefore, we primarily relied on the EV/R&D multiple, which is the most reliable metric for acquisitions involving pre-revenue pipelines. Across the five transactions analyzed, EV/R&D multiples ranged from approximately 4x to 81x, with an average of around 29x and a median of about 22x. This highlights the considerable amount strategic buyers are willing to pay per dollar of R&D for high-potential metabolic assets.

By applying the average and median EV/R&D deal multiples to Metsera’s projected 2024 R&D expenditure of $107.5 million, we derive implied Enterprise Values of approximately $3.1 billion (based on a 29x average multiple) and $2.4 billion (based on a 22x median multiple). Adjusting for Metsera’s essentially neutral net debt position results in a comparable equity value range of $2.4 billion to $3.1 billion based on precedent transactions.

The valuation derived from precedent transaction multiples is significantly lower than both our intrinsic rNPV estimate and Pfizer’s acquisition offer. This outcome is expected and highlights the structural limitations of using deal multiples when evaluating early-stage biotech assets. First, most transactions in our sample involve companies that are at earlier or less de-risked stages than Metsera, typically characterized by limited data packages, narrower pipelines, or lower differentiation. This results in lower EV/R&D multiples and depresses the implied valuation when applied to Metsera. Second, these transactions do not take into account Metsera’s stronger Phase 2b efficacy data, its advanced readiness for Phase 3 trials, or the significantly improved commercial outlook for GLP-1 obesity drugs. Third, precedent-multiple valuations fail to capture strategic value. In contrast, Pfizer’s bid explicitly includes synergies, benefits from competitive positioning, and the opportunity to secure a scalable next-generation GLP-1 backbone. These factors are internal to the acquirer and are absent from historical transactions, which is why Pfizer’s offer is justifiably much higher than the levels suggested by generic deal multiples.

For these reasons, the transaction-multiple approach yields a conservative valuation range of $2.4–3.1 billion, which is well below the rNPV intrinsic valuation of $5.5–6.0 billion and Pfizer’s strategic offer of approximately $10 billion.

Conclusions

The rNPV valuation, which accounts for the probability-adjusted success of clinical trials, realistic commercialization economics, and long-term cash flow generation, provides the most credible estimate of Metsera’s intrinsic value, ranging from $5.5 to $6.0 billion. In contrast, public trading multiples suggest a significantly lower valuation of $1.6 to $3.5 billion. This discrepancy reflects the structural undervaluation of pre-revenue biotech companies in public markets, where clinical uncertainty, dilution risk, and the absence of near-term revenues depress enterprise values. Similarly, precedent transaction multiples offer a conservative valuation between $2.4 and $3.1 billion, as historical deals typically involved earlier-stage or less differentiated metabolic assets and do not account for Metsera’s robust Phase 2b data, readiness for Phase 3, or platform optionality.

Among the three methodologies, the rNPV approach is the most reliable for Metsera’s profile. It directly models the economic value of its drug candidates throughout their entire patent-protected lifecycle, while also explicitly factoring in clinical risks. Trading and deal multiples tend to be backward-looking, failing to reflect Metsera’s unique scientific profile, differentiation, and development momentum. In contrast, rNPV is forward-looking and aligns with the decision-making frameworks used by strategic acquirers. Pfizer’s $10 billion offer, including contingent value rights (CVRs), exceeds the rNPV estimate but is consistent with the strategic premiums often observed in late-stage biotech mergers and acquisitions. This price reflects not only Metsera’s probability-adjusted cash flow potential but also the synergies, competitive positioning, and long-term strategic value that Pfizer seeks as it accelerates its entry into the rapidly expanding GLP-1 obesity market.

Market Overview

Macroeconomic Trends & Broader Context

Underlying Issues

One in eight people on Earth now lives with obesity. A small part of that statistic can be accounted for simply by genetic determinism, yet for many of us, obesity stems from the cumulative effect of living in environments that make weight gain effortless and weight loss unusually difficult. Cheap, calorie-dense food is more convenient and easier to find than healthier alternatives. Modern-day urban planning envisions car-centric infrastructure in cities across the globe, forgoing the frequent brisk walks that had dominated man’s routine for much of the 20th century. Office jobs keep people tied down to their chairs and laser-focused on their screens. The result has been a slow, steady drift toward a sedentary baseline, visible across age, geography, and income.

These simple acknowledgements of our daily lives are backed by a growing body of formal research studies on the subject. In 2022, the World Health Organization reported that only two in three adults met minimum physical-activity guidelines. That decline aligns closely with urbanization trends: between 1984 and 2024, the share of people living in cities climbed from 41% to 58%, and the rhythm of daily life shifted accordingly. Everyday tasks that once required leaving the house, such as shopping, banking, or even basic errands, have now been absorbed by the digital economy. A decade ago, the default was walking to your local grocery store; today, it is tapping ‘order’ on a delivery app.

Diet has moved in the same direction. In a two-year U.S. study, it was observed that roughly 55% of all our consumed calories come from ultra-processed foods. Globally, the market for these products is expected to grow 40% over the next decade. These foods are engineered for shelf life, low cost, and instant appeal, high in fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates, and low in nutritional value. They are also, in most places, cheaper than healthier options. Ironically, the price gap that made obesity a condition of the wealthy in medieval times has now inverted. Today, obesity disproportionately affects lower-income, working-class households.

The through line across these lifestyle changes is friction, or rather, a distinct lack of it. Modern life removes the small physical efforts that once kept weight in check while flooding our diets with options scientifically designed to keep you eating as much as possible, for as long as possible. Obesity is not simply a matter of individual choice; it is the predictable outcome of systems that make certain choices far easier than others.

Obesity Data Worldwide

Obesity is commonly measured at the population level using the Body Mass Index (BMI). It is understood as a surrogate marker of the level of adiposity, which puts a person’s weight and height in relation (weight/height).

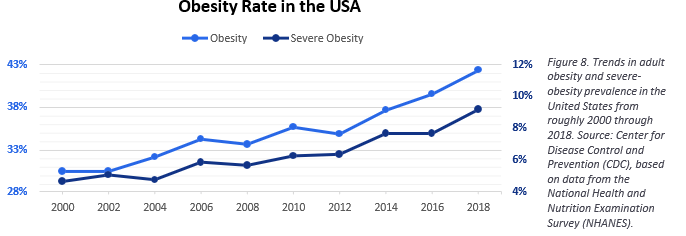

Obesity’s global rise has been uneven, but the United States sits near the top of the curve. High-fat, high-sugar foods are cheap and omnipresent, and the effects show up starkly in national health data. In 2000, 30.5% of U.S. adults over 20 met the clinical threshold for obesity; by 2018, that figure had climbed to 42.4%, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. The Global Obesity Observatory now ranks the U.S. 19th worldwide, surpassed mainly by small Pacific Island nations and wealthy Gulf states like Kuwait and Qatar.

The pattern is not limited to the U.S. Many of the countries in the top half of the global ranking are emerging economies in South America and the Middle East, where urbanization and income growth have shifted food consumption toward convenience and calorie density. In contrast, developed Asian economies such as China, South Korea, and Japan appear at the bottom of the list. Cultural norms around portion size, dietary composition, and active commuting still act as structural brakes

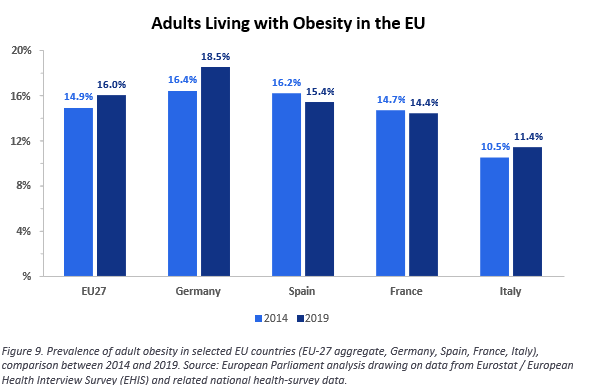

Europe falls somewhere between these extremes. The 2019 European Health Interview Survey reported that 16.5% of EU adults lived with obesity and 36.2% were overweight. Across the broader WHO European Region, obesity has more than doubled since 1975, rising from 10% to 23% of the population by 2016. The implications go beyond individual health. The OECD estimates that obesity will reduce life expectancy in the EU by 2.9 years over the next three decades. If the trend holds, OECD countries could end up spending up to 8% of their total health budgets on obesity-related diseases between 2020 and 2050, much of it on chronic conditions like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers, as well as the indirect losses tied to reduced economic productivity.

The economic costs of obesity are already measurable at the national scale as a proportion of total GDP. In 2020, the cost of obesity and overweightness ranged from about 1% of GDP in African countries to more than 3% across the Americas. By 2060, those numbers are expected to rise to 2–4% in most regions, and more than 5% in parts of the Middle East. Across the 161 countries analysed in a recent study, overweightness and obesity are projected to absorb over 3% of aggregate global GDP by 2060.

Fighting Obesity

Over the past two decades, governments have begun treating obesity less as a collection of individual choices and more as a policy problem with measurable economic and health consequences. Europe has been one of the most active regions in this context. Since the early 2000s, the EU has pushed for measures that discourage high- sugar and high-fat consumption, nudging the food environment toward something closer to public-health goals.

A notable example came in February 2022, when the European Parliament called for a mandatory, science- based nutritional label across the Union to help consumers gauge the health profile of packaged foods at a glance. By then, France had already moved in that direction. In 2017, it adopted Nutri-Score, a colour-coded front-of-pack label that grades products from a green “A” to a red “E.” The system spread quickly: Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and several other member states have since adopted or endorsed the label. France’s early results are not exactly game-changing, but they are nonetheless meaningful: France is one of the few European countries that has seen obesity rates edge downward over the past decade.

Labelling was only one part of the toolkit. EU institutions also encouraged member states to use pricing policies to shift consumption away from high-sugar and high-salt foods. Ten European countries now tax sugar- sweetened beverages, and France again led the way. It introduced such a tax in 2012, then strengthened it in 2018 by making the tax rate progressive in relation to the quantity of sugar. The policy successfully achieved its intended effect, with countries that have implemented the policy noting lower sales and reduced intake of sugary drinks.

It is crucial to note that the EU tends to ‘play safe’ when implementing many of its policies, adopting what is called ‘the precautionary principle.’ The implication is that if there exists even the smallest probability that an ingredient might be harmful, it is immediately banned or restricted until proven otherwise. The U.S, on the other hand, generally recognizes most additives as ‘safe’ up until the FDA identifies a problem, which leaves far more substances in circulation. The difference is visible on the shelves. Europe’s food industry has had to reformulate thousands of products to comply with EU standards; the U.S. market, by comparison, allows a far wider range of artificial dyes, preservatives, and processing agents.

None of this implies that Europe’s supermarkets are anything akin to a temple of health, but the cumulative effect of these policies is clear: European consumers, on average, encounter fewer ultra-processed ingredients and fewer high-risk additives in their day-to-day food basket than their American counterparts.

Historical Evolution of Obesity Drugs

The first attempts to treat obesity pharmacologically date back to 1893, when physicians began prescribing thyroid hormone to raise the body’s metabolic rate. The treatments produced modest weight loss but came with predictable and often severe consequences, including heart palpitations, muscle wasting, and thyrotoxicosis, which were common enough for the approach to be abandoned (George A. et al., 2022).

Centrally acting sympathomimetics, such as the amphetamine derivatives deoxyephedrine, phentermine and diethylpropion, were among the earliest pharmacological agents used specifically for weight loss (Colman, 2005; Wilding, 2007). These drugs were popular in the 50’s and 60’s but they became less used starting in the early ’70 when cardiovascular risks were noted. By the 1980s, they were largely overshadowed by the serotonin (5-HT) releasing agents. It was known that these drugs could produce primary pulmonary hypertension, however the tolerability was considered acceptable at the time. Within a short few years, reports of serious cardiac side- effects started to rise (Connolly et al., 1997), and the complications were even more serious when these agents were combined with phentermine. As a result, they were soon taken off the market.

The early 2000s introduced another wave of anti-obesity candidates: sibutramine, rimonabant and orlistat, each targeting different metabolic levers. Sibutramine, a norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor, initially appeared to offer modest weight loss with manageable risks, but long-term use revealed cardiovascular hazards, and the drug was withdrawn in 2010. Rimonabant, a cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, suppressed appetite and was found to produce a placebo-subtracted mean weight loss of 4.6 kg over a one-year dosing period, but it triggered psychiatric side effects, including depression and suicidal ideation. It was never approved by the FDA, and was removed from the European market in 2008. Finally, Orlistat, approved in 1998, took a different approach. Unlike the other weight loss agents, it inhibits pancreatic lipases, reducing fat absorption from the gut by ~30%. Weight loss was considered relatively modest, but it avoided the cardiovascular risks that had plagued earlier drugs. However, it instead introduced gastrointestinal problems that limited adherence (Recasens- Alvarez et al., 2025).

The genuine turning point came in 2005 with the approval of exenatide (Byetta), the first GLP-1 receptor agonist. It was a twice-daily injectable diabetes drug, not an obesity therapy, but clinicians quickly noticed that patients were losing weight even without deliberate lifestyle changes while on the drug. Novo Nordisk extended the concept with liraglutide in 2010, whose longer half-life enabled once-daily dosing and better tolerability, and by 2014, Novo reformulated it as Saxenda, the first GLP-1 therapy explicitly positioned for the obesity market.

Even so, daily injections limited how far early GLP-1s could spread. Side effects, especially nausea, resulted in dropouts being commonplace, and costs for the medication remained high. Meanwhile, another gut hormone was under quiet investigation: amylin, a peptide co-secreted with insulin. In 2005, the FDA approved pramlintide (Symlin), an amylin analogue. Its multiple daily injections and modest weight-loss profile kept its use-case scenarios narrow, but it validated the biological principle that would later make dual-agonist therapies possible: combining hormones with complementary mechanisms can produce stronger and more stable metabolic effects than targeting a single pathway.

Widespread adoption finally arrived with Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide (Wegovy), which was approved for obesity in 2021. Presenting a ~15% placebo-subtracted mean weight loss and a highly favorable cardiovascular profile, semaglutide entirely shifted expectations of what a great weight-loss drug could achieve. It was soon followed by tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 agonist from Eli Lilly, that delivered an even greater efficacy of ~20% mean weight reduction at higher doses and generally improved tolerability.

Together, these two compounds now generate ~67% of global obesity-drug sales, a concentration that reflects not only their efficacy but also how few other treatments ever made it this far. After more than a century of experiments and failures, the obesity market has finally found its ‘miracle drugs’ that produce reliable, clinically meaningful weight loss, and, just as importantly, fit into a chronic-disease model where patients stay on treatment long enough to matter.

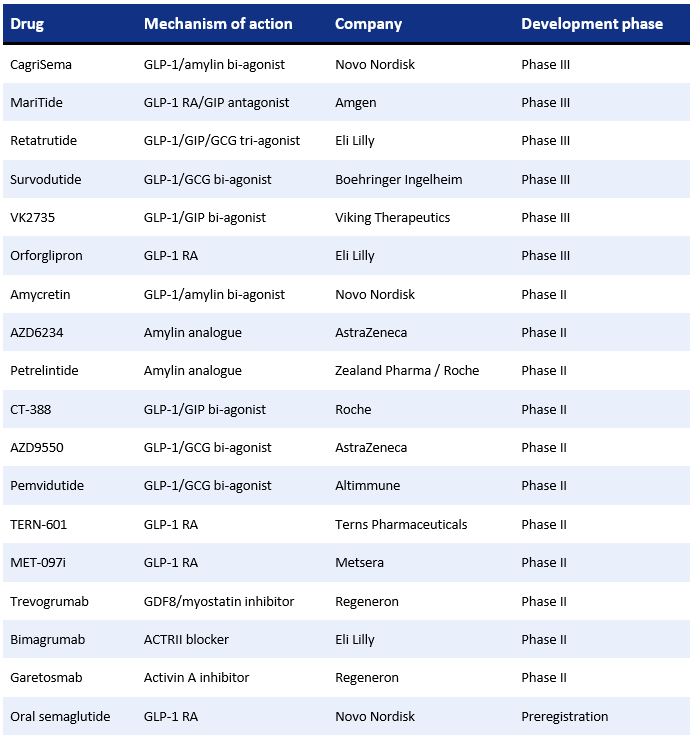

Though semaglutide and tirzepatide represent a major leap forward for the market, their success has also revealed the remaining challenges. Weight-loss plateaus, poor ‘quality’ of weight loss, and muscle mass reduction are driving forward the development of the ‘next-generation’ agents with novel mechanisms and improved pharmacology. Many are designed to complement and build on GLP-1-based therapies. Carles Recasens-Alvarez of Nature Review selected 18 main drugs in development, currently in mid- to late-stage trials, that make up the landscape of emerging therapies within the obesity market:

Obesity Treatment Market

Historical, Current and Future Market Size

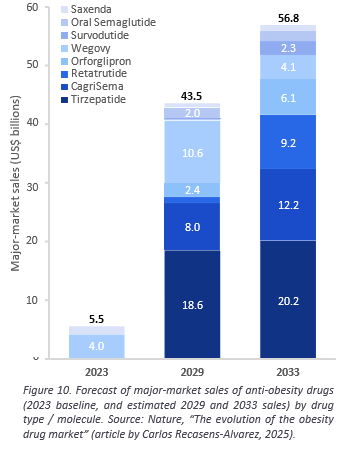

Over the past three decades, the obesity drug market has seen a major shift. Initially suffering from significant tolerability setbacks and low efficacy up until the late 2000s, it has now turned into a hyper-attractive market for pharmaceutical companies, with a massive projected market size, a total addressable market on the scale of billions of people, and increasingly competitive drug formulations. Unsurprisingly then, large-cap pharmaceutical companies from around the globe are looking to go on a massive shopping spree over the next few years in a desperate scuffle for market share.

In 1960, when the first anti-obesity drugs were commercialized, the entire U.S. prescription-drug market, every therapy combined, was estimated to be valued at around four to six billion dollars. The modern obesity-drug market alone is now larger than that, and its trajectory is steeper. Demand is no longer limited to small specialist populations, and the business model has shifted from short courses to long-term management.

The inflection point was, of course, the arrival of GLP-1 receptor agonists, which introduced a level of reliability that earlier drugs never achieved. Novo Nordisk was the first to establish category leadership with liraglutide, launched to market in 2010 under the brand name Victoza. At the time, Victoza boosted Novo’s net income up 23%, with more than $200 million in North American sales in its first year. This initial launch set the pace for the evolution of the obesity market. The catch for rivals was immediate: 15–20% of Victoza users were switchovers from exenatide (Byetta), Eli Lilly’s earlier GLP-1 (Victoza Launch Boosts Novo Sales, Fierce Pharma, 2010).