“The Constitution imposes no obligation on the States … to pay any of the medical expenses of indigents” US Supreme Court, 1977

The US is the only industrialized nation with selective healthcare coverage, meaning that basic healthcare services are not provided to everybody and paid for by the government (or government-managed entities), and this has led to the development of an insurance-based market populated by both private and public players. A modified “version” of the so-called multi-tiered system is in place where, unlike the most common and widespread version of it where basic needs are granted to the general public and then further, more “advanced”, services can be privately paid for, only certain Americans are eligible for government-sponsored health insurance plans, namely Medicare and Medicaid, which were both created in 1965 in response to the inability of older and low-income groups to buy private plans.

More specifically, Medicare covers for citizens and long-term residents aged 65 or above and for those affected by severe disabilities, irrespective of income. Medicaid, on the other hand, caters to the very low income slice of the population. Even a combination of the two is possible, the so-called “dual coverage”. As of 2015, around 20% of Americans are enrolled in the Medicaid program (which is not however available throughout the country), while 14% benefit from Medicare. It is also worth mentioning the government provides also for veterans, their families and survivors through dedicated medical centres and clinics, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) program.

Almost half of the population (49% as of 2015, and more than 55% of those younger than 65) receives coverage through its own employer or a family member’s one (family plan) as part of the compensation’s “benefits pack”. It is worth noting how costs for employer-paid health insurances rose rapidly between 2001 and 2006 (63%, while inflation rose in the same period by 14% and wages by 15%), then started to “lose steam” in the 2006-2011 time frame (31% increase vs 12% for inflation and 16% for wages) and finally, between 2011 and 2016 (so since the ACA was implemented), they just rose by 20% (inflation by 6% and wages by 11%. This slowdown in the growth pace can be partially explained by employees switching to lower quality plans (higher deductibles, greater number of conditions not covered by the new policies) that acted as a drag on the average price increase of plans.

For those who do not fall into either one of the previously mentioned categories, they must pay for treatments out of their own pocket by buy coverage in the individual market, i.e. on or off the “exchanges” (a regulated venue to trade insurance plans and where buyers can claim for a premium tax credit), where an array of plans is usually available, and they differ according to the percentage of costs that will not be covered by the insurance company (i.e. co-pay), deductibles, … Evidence shows that the majority of off-the-exchange plans tend to be cheaper ones (not necessarily more convenient, as they usually have higher co-pay and deductibles), but more than half of them offer some sort of out-of-network coverage, against just 36% of those plans sold on the exchanges. This means that they are more flexible and implicitly offer more choices, as the beneficiary will be able to receive assistance also in hospitals not linked to the specific network of the insurance company he bought the plan from, without having to pay a significantly higher percentage of the costs with his own money.

Finally, as of 2016 around 9% of the US population lacks any form of medical coverage. The primary reason for being uninsured appears to be related to the low income of those families with at least a working member or individuals who however earn more than the Medicaid threshold. In these cases, the major barrier to coverage is represented by unaffordable premiums or onerous economic conditions coming with the plans (co-pay, deductibles,… as stated before).

Focusing on healthcare facilities in general (specifically community hospitals, which represent almost 90% of all structures meeting the American Healthcare Association’s criteria), they are mainly run by private companies. Of these, slightly more than half of them (58%) are not-for-profit businesses, 21% are for profit while around 20% of the hospitals are state/local government owned.

According to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), as of 2015 the United States spent $9,451 per capita on healthcare, topping the worldwide list (which it has dominated for the last 15 years), with the closest group of “followers” paying almost $3,000 less (with the exception of Luxemburg being in between).

Also the total expenditure as a percentage of total GDP appears significantly larger than other developed countries at almost 17%, and the same goes for the share of costs covered privately.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, healthcare has been subject to intense scrutiny by both democratic and republican candidates. Ms. Clinton focused her campaign on the expansion of Medicaid to those states (19) who still have not adopted it, on the implementation of measures aimed at limiting arbitrary and unjustified hikes in health premiums and on capping costs for out-of-pocket and prescription drugs. Mr. Trump promised on the other hand to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act put in place by president Obama (aka Obamacare). He stated his goal was to do away with the “artificial lines” forcing people to buy coverage in their own states and the skyrocketing premiums affecting certain areas of the country (see the following sections on this) while avoiding anyone who benefitted from Obamacare being excluded from health coverage or being worse-off financially. Regarding drug pricing, he promised he would have Medicare and Medicaid negotiate prices with drug companies directly instead of having to accept the intermediation of insurance companies (promise that as of today has been ditched entirely).

DRUG PRICING

Being one of the main reasons why healthcare is still so much more expensive in the US, the price-gouging issue became one of the thorniest controversies over the last few months of the campaign, both because the cost of drugs has been on the rise for most of the last decade and eating up an ever-larger share of overall medical costs (now over $350 billion annually), but also because of the notorious “Daraprim” price-gouging scandal involving Mr. Shkerli, CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, a small drug company, who raised its price from $13.5 to $750 a tablet overnight (+5,500%), citing as a main reason that “money from the price increase will go toward research on new drugs”.

Per capita prescription drug spending in the United States is currently the highest in the world indeed, and is largely driven by brand-name drug prices having risen in recent years at rates far beyond inflation. The most crucial factor allowing manufacturers to set high drug prices is market exclusivity, protected by monopoly rights awarded upon Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Specifically, high drug prices have been the result of the decision by the US government to grant “monopolist status” to drug manufacturers. As a first consequence, drug manufacturers in the US are allowed to set their own prices without any form of negotiation, and that is crucially different from everywhere else in the world. In fact, countries with national healthcare programs have government-backed entities either negotiate drug prices or decide not to cover drugs whose prices are deemed to be excessive. Secondly, in an effort to promote innovation, the US have implemented a patent system allowing drug manufacturers to remain the sole legal manufacturer of a specific drug for 20 years or more. The FDA also gives drug manufacturers exclusivity for certain products, including those that treat people with rare diseases. To make things worse, drug companies sometimes deploy questionable strategies to maintain their monopolies, studies show. The tactics vary, but they include slightly tweaking the non-therapeutic parts of drugs, such as pill coatings, to game the patent system, or paying large pay-for-delay settlements to generics manufacturers who sue them over these patents.

Notably, specialty drugs have seen the most dramatic rises, oftentimes motivated by reasons strikingly similar to Mr. Shkerli’s. These drugs include some of the most recent, advanced and complex drugs available on the market used to treat rare or complex conditions such as cancer, HIV, … Consequently, they tend to cost way more than regular medications (even north of $80,000). Being however necessary to patients with those specific diseases, the pricing issue was heartfelt by the general public and, also in wake of the “Daraprim” news, was directly addressed by the then frontrunner candidate Clinton in a tweet: “Price gouging like this in the speciality drug market is outrageous. Tomorrow I’ll lay a plan to take it on.”

Clinton’s comment on Twitter (on September 21, 2016, yellow line) sent the 144-member Nasdaq Biotechnology Index down 4.7%, and as polls showed her as the likeliest winner of the elections, rising concerns probably pushed the index further down. After her surprise defeat, most of the losses were temporarily recovered, even though the index lost some ground in December again (as of today, the index has however recovered completely. For this graph please see the last section of the article).

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT & ITS INNOVATIONS

Obamacare, also known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), is a law signed on March 23, 2010 by president Barack Obama, with the aim of reforming the health insurance industry and the American health care system as a whole, while giving Americans more rights and protections and expanding access to affordable quality health care to tens of millions of uninsured. The law is extremely complex and includes several provisions, which came/will come into force in a phased fashion between 2010 and 2020, even though the bulk of the act took effect in 2014.

The first main pillar is the prohibition by insurers to deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions (before 2014, some policies would not cover expenses related to them). Equally important was the introduction of the so-called “Ten Essential Health Benefits”, which are since 2014 mandatory for every new plan under ACA (They consist of ten categories of items and services required for all individual and small group plans, and include items such as maternity and new-born care that have been traditionally disliked by insurers).

Medicaid was also expanded to include families and individuals with an income up to one third more than the Federal Poverty Level (including the 5% “income disregard”, the limit is 138% of the FPL). This provision especially benefitted childless adults that were previously excluded irrespective of their income. This point was challenged before the Supreme Court in 2012 (who also ruled on several other aspects of the law) but was upheld, even though the federal government’s ability to penalize states that did not comply was significantly limited. This second pillar’s optionality notwithstanding, 32 states have decided over the years to opt-in, and studies have estimated this norm’s contribution in terms of additional insured people to be more than 10 million Americans (around half of all Americans who gained coverage under the ACA). It should be noted that this widespread expansion has been heavily incentivised by the federal government paying 100% of the additional costs until 2020 (then 90%).

The third feature was that dependents (sons & daughters) younger than 26 were allowed to remain on their parents’ insurance plan even if (among other conditions) they got married, had children or were not tax dependents anymore.

American individuals and families with incomes between 1 and 4 times the FPL were also made eligible to receive federal subsidies through tax credits in case they purchased plans on the exchanges.

To avoid the notorious “death spiral issue” (where starting from a standard random population of insured people, the healthiest groups tend to subsequently drop out if they deem the expected costs of the premiums to outweight their healthcare future expected costs, leaving an ever sicker and smaller group that will see their premiums increase exponentially until no body is insured anymore), the ACA intrduced the “individual mandate” for all those not covered by their own employer, Medicare or Medicaid (or other public programs). This meant that all Americans who could afford but chose not pay for their own insurance faced a penalty when filing the following round of federal tax returns.

A similar provision , called the “employer mandate”, was introduced too. Businesses with over 50 full-time employees faced tax penalties in case they received healthcare subsidies of any kind in the past and decided not to comply with this mandate of compulsory insurance for the employees. This provision proved (and still is) to be quite complex and controversial,, as several businesses “started wondering” whether it made more sense to extend coverage to all employees as required or pay the penalty (or even more extremely to discontinue existing plans altogether). In fact, due to the interplay of insurance policies available on the market and those provided by employers (price dynamics in particular), as well as the complex penalty mechanism (e.g: a penalty is also imposed on the employer even in case it actually does provide insurance, but that policy is found unaffordable by the employees who have then to receive marketplace subsidies), it has been alternatively claimed for years (but with limited evidence) that this provision would have been a job killer, leading to higher labour taxes or to reductions in healthcare benefits provided by employers.

Other major provisions contained in the ACA stated that insurers could no longer cancel coverage for any reason aside from non-payment or fraud. This was a major change, as it used to be common practice for insurers to stop covering for patients due to even small mistakes in the application form (even retroactively) once they became too expensive to provide for. Moreover, a yearly cap on the out-of-pocket payments was set (once surpassed, there is no longer co-pay). Medicare was improved for seniors and those people with long-term disabilities. Insurance companies could also no longer raise premium payments without states’ approval. Finally, as stated in the previous section, the system of the exchanges was set up with this law.

Obamacare has been heavily criticised since its inception and has always been controversial. After the law was signed in 2010, Republicans launched several legal challenges. As briefly mentioned before, in 2012 the US Supreme Court declared the ACA to be constitutional and only marginally modified it with a 5 to 4 vote.

During the presidential campaign, republican candidate Donald Trump included terms like “disastrous” and “failing” when referring to the ACA. Among the most frequently used argumentations against ACA were the high complexity of the law, as it was said that it made already-confusing health care and insurances even harder for the average American to understand. Moreover, the principle of having a penalty tax levied on those unwilling to purchase a plan was tough for many to understand. ACA came also under fire for having increased health care costs in the short term. That is because many people received preventive care for the first time in their lives and medical tests tend to be very expensive (it should be noted however that data suggest over time Obamacare’s individual marketplace improved also pricewise and became financially “healthier” as more people enrolled).

THE AMERICAN HEALTHCARE ACT

Ever since the 2012 GOP primaries, right after the Supreme Court ruling on ACA, Republicans seemed to agree on a high-level agenda for how healthcare should have been reformed: a financial transformation, aiming in particular at reducing social programs for low-income individuals, capping Medicare subsidies (they are currently almost fixed at 70%, irrespective of the absolute total cost of the insurance policy) and limiting the federal-funds-fueled expansion of Medicaid.

After promising substantial changes to the current law during his campaign, president Trump’s American Health Care Act (AHCA or Trumpcare) has become one of the major early goals of his presidency. On March 24, 2017, however, after days of intensive negotiations to satisfy the multiple “currents” within the republican party (and the Freedom Caucus in particular), a vote on this bill was pulled from the lower chamber of congress after becoming clear that not enough members of the House of Representatives would have voted in favor. This became a great reason for embarrassment within the GOP, as the AHCA version that in the end did not face the vote was already the result of several compromises that even led president Trump to admit there existed “things in this bill that I didn’t particularly like”. As a revised version of the law is still expected to come under congressional scrutiny in the next months, it is worth analyzing its main features as well as the reasons that made it so unpopular even within the republican ranks.

First, the AHCA would have retained the two most popular Obamacare features: the possibility for young adults to stay on their parents’ plans and, more importantly, the possibility for those with pre-existing conditions to get comprehensive insurance.

Another series of provisions focused instead on tax reforms. These included the removal of the penalty taxes on both those employers that did not extend/provide insurance to their employees and those individuals who were not enrolled in any plan (the so-called “mandates”, as covered in the previous section). As previously noted, making it compulsory to have insurance was a provision of the ACA specifically targeting the “death spiral issue”, as it allowed insurance premiums to remain at relatively low levels, which then translated into more people being able to get coverage. Just as a reminder of what detailed in the previous section, lower premiums are possible as insurance companies, applying the diversification principle, use the premiums from the entire pool of “clients” (including healthy ones) to pay for the sick portion of them, and it can be clearly seen that this diversification would be impossible should not enough healthy people be enrolled. AHCA critics lamented indeed that by removing the mandates, this would have in essence incentivized people to wait until sick and then to enroll, triggering the very first steps of the death spiral.

It should on the other hand be noted that under the ACA, premiums for the healthy portion of the population actually increased, as they were partially used to fund the expenses of sick Americans. As this fact made the ACA unpopular in this category of people, the AHCA tried to be a response to these concerns. Regarding the serious death spiral shortfall, however, and to keep some sort of incentive for enrollment, the AHCA included a compulsory premium increase (up to 30%) for those people who opted out of an insurance policy and then reapply for coverage after being without it for more that 63 days. This solution did not actually appear to solve the problem, as an healthy person would just let his insurance lapse to avoid the future price uptick.

Other provisions aiming at keeping premiums under control, at least for the healthier portion of the American society, included allowing insurers to charge elderly people as much as 5 times more than young people (under the ACA the limit is 3 times).

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued in March a report projecting, under the AHCA, that about 52 million Americans will become uninsured by 2026, and this translates in a 14 million increase. This result would have certainly not been in line with the initial promise of then candidate Trump, as he oftentimes said during his rallies that no one “will be left to die on the street”.

Another area of intervention was the tax credit structure introduced by the ACA. While Obamacare tax credits were based on the cost of the insurance plan itself, Trumpcare would have introduced a flat tax credit based on age (it would increase as a person gets older), clearly downplaying cost of living and insurance premium differentials between different regions of the USA. The tax credits would have also been phased out for those earning over $75,000 a year. Critics noted how under the AHCA a generalized increase in the cost of individual plans would have been a natural consequence, with the young, healthy people being the only likely exception.

Another controversial tax-related aspect was the elimination of taxes on high-income citizens (who would have no longer had to pay the additional Medicare tax introduced with the ACA). This provision would have however impacted the federal deficit as well, as it would have amounted to a whopping $460bn over a 10 years period, and this is likely one of the reasons leading the debt-concerned conservative wing of the GOP not to back the plan.

Under the AHCA, also Medicaid was set for a significant revamp. Considering its expansion has been “hands down” one the most successful provision in terms of the sheer number of uninsured Americans who obtained coverage thanks to it, the Medicaid reform spurred a great debate in the US. The new law proposed by republicans would have phased out its expansion, and after 2019 newly eligible Americans would have not had the possibility to be added. It would have also stopped the federal government from directly paying a large share of the expanded program, and these funds would have been instead handed out to the states as a form of block grant. While the reasoning behind this innovation was to make states more efficient in their use of funds, it would have also meant that Medicaid would have had to compete for funds against other priorities within each state (a similar fund drain happened in the past with the deinstitutionalization of community mental health care centers, where the lack of sufficient resources meant there were not enough centers to serve those with mental health needs). Additionally, the AHCA included a further provision imposing a small monthly fee to be paid by Medicare recipients for the services. Critics noted however that this would have likely lead to an increase in the general costs of health care and resulted in major hospital groups opposing the plan: indirectly restricting (consequence of higher costs) access to primary care physicians would have in fact meant an increase flow for (more expensive) emergency hospital rooms.

Following a similar reasoning, the AHCA also included the elimination of federal funds for Planned Parenthood, a provider, among others, of abortion services and access to contraceptives. This would have potentially been followed by an increase in abortions in the short term, and this aspect is another motive that led some members of the GOP to oppose the AHCA.

All in all, the AHCA was disliked by many. Only 17% of the American electorate was actually in favor of the plan. And while some republicans saw it as a first test for Trump’s presidency (in the words of Dana Rohrabacher: “If we vote it down, we will neuter Donald Trump’s presidency … We are not going to undermine the president’s ability to get things done”), this was not enough to convince the necessary number of representatives to support it. While the Democrats were clearly against it as they claimed the republicans’ obsession with Obamacare was a not-so-disguised attempt to attack the credibility of Obama and the Democratic Party, it was striking that even most Republicans were against it. Aside from the reasons already mentioned in this piece, many wanted an even more radical proposal, with a complete rebuke of all ACA regulations, starting with the possibility for people with pre-existing conditions to get insurance coverage.

From a merely technical point of view regarding what happened in the days leading to March 24, 2017, the bill would have not passed the vote of the House of Representatives due to the Freedom Caucus group, a portion of the republican party who would have supported the bill only if it also included a provision to eliminate the 10 essential health benefits requirement as well as the community ratings. The first change would have allowed for the creation of lower-cost plans but, consequently, would also have increased premiums for those plans still including all 10 of them. The second potential change would have restored a normal practice among insurers stopped by the ACA: the individual rating of each policyholder leading to an individual premium based on expected future costs. The obvious consequence would have been an increase in healthcare costs for the sicker portion of the population (note that under the ACA, ratings need to be done on a specific community of people irrespective of health status). These two provisions were in the end deemed too unpopular to be included in the bill, even though current talks among policymakers eying a compromise among all GOP factions before a potential future vote on this matter, are said to be including also the addition of these two requests in the new healthcare bill.

PRESENT AND FUTURE OF THE ACA

“We declared that in America, health care is not a privilege for a few, but a right for everybody”. These were the words used by president Barack Obama in its opening speech for the 7th anniversary of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This act has arguably been its greatest legacy and has led to more than twenty million Americans gaining an insurance coverage. As of today, more than 90 % of Americans are insured, the highest percentage in America’s history. But even since ACA’s enforcement in 2010, and certainly during the 2016 presidential campaign, the law has been subject to heavy criticism. In this section we focus on one of the major discussion points, namely whether Obamacare is structurally unsustainable from a financial stand point for the government and whether, as Mr. Trump frequently says, it will eventually explode on its own. “The general consensus is that the law is actually not collapsing” recently said Larry Levitt, senior adviser at the Kaiser Family Foundation and former senior health policy adviser to the White House.

The first major talking point of the ACA’s critics regards the skyrocketing premiums in the marketplace. It is indeed true that insurance policy’s prices have been on the rise over the last 12 months, but the reason behind it appears to be higher-than-expected medical claims from patients rather than a fallacy of the law itself. This phenomenon is moreover not widespread, as cheap plans (below $100 a month) are still available in most states. What should also be born in mind is that only around 5% of Americans rely on the marketplace (on or off the exchanges) to buy their coverage, as they usually are eligible to apply for Medicaid or Medicare or receive coverage through their employers. As detailed in the sections above, this last option if by far the most common, and healthcare costs for employers have been rising at a remarkably low pace since the ACA came into force (for specific data please see the first section). A similar slow uptick in price has been observable for Medicare recipients too.

It is however important to further analyse the individual market, and to note how insurers have been struggling to turn the ACA new coverage options into a profitable business, as the most expensive clients oftentimes find ways to enrol only when they need to face large medical bills, and also given that most premiums have been set artificially low in the first years of the ACA. Regarding the former issue, the health department has already issued a new set of guidelines for 2018, tightening enrolment rules, to prevent people from dropping from a plan right after the insurance has paid for high medical bills.

When ACA detractors, and in particular Mr. Trump, state that the law is exploding, they are specifically referring to the individual markets (the other programs affected the ACA are supported with federal funds and therefore can not technically collapse). In this market, premiums have indeed risen significantly (by an average of 25% for so-called benchmark plans, but with outliers as Arizona where the increase has been around 116% over the last year) while the choice selection has declined, to the point where states like Oklahoma and Tennessee are expecting to have zero remaining insurance companies offering plans for the individual market by 2018. According to a Bloomberg analysis, most insurers in this market have been losing money for the last three years and this has been the main driver behind the decision to pull back. The quickest (but controversial and not necessarily the easiest) solution would be to increase premiums, but this will depend on how the new Trump administration will reform the ACA and change the individual market. There also appears in fact to be a structural problem in the exchange market, as not enough “private money” (from clients) is available, and without some forms of federal funding, similarly to Medicare, the extremely high costs of covering for the sickest portion of the population could lead to excessive premiums potentially leading to a death spiral even with the “mandates” provisions, as it could turn out to be more convenient to pay the penalty tax indeed.

A final crucial additional source of uncertainty is whether the “mandates” will be kept under a new AHCA, and until this is clarified, insurance companies will be unable to decide whether to participate in all states’ individual markets or not.

To avoid a major retreat from the individual market of several major insurers (which, unless the current situation changes, is set to happen in 2018, significantly reducing choices in a number of states), some urgent reforms appear to be fundamental. Improvements such as eligibility verification, more rigid special enrolment periods, approval from state regulators or higher premiums are among those interventions that could prop up this market.

THE STOCK MARKET REACTION

Since his election in November (green line in graphs below), the expectations of lower taxes, deregulation and increase in government spending promised by Trump have proven to be a boon for the stock markets, with record-setting performances (fifth best gain in history in percentage terms (4.02%) in his first 30 days of office).

However, as it became clear on March 24, 2017 (red line) that the AHCA would have not had the necessary support in the House of Representatives, markets appeared to readjust their expectations of Trump’s odds of being able to enact some of the key reforms he promised during his campaign. Influenced by the president’s inability to muster enough votes for his effort to repeal and replace the ACA, market operators have started to doubt his ability to push his ambitious “reformist” agenda through.

Analyzing the performances of some of the most common indexes, it is indeed possible to note how both the S&P 500 and the Dow J.I.A. lost most of their momentum in March 2017, and it could be argued that uncertainty about the ability of the president to promote his economic agenda has weighed operators’ optimism regarding the US economy down.

Regarding the Nasdaq Biotech Index, after the spike following Mr. Trump election noted in the first section of this article, it consistently lost ground over the last two months of 2016, only to recover all its losses by early March 2017, days before the AHCA vote flop. Even though the main drivers of this index are probably related to the general economic outlook for the US and also partially by the decision of the president not to push forward with his promise to have government agencies directly negotiate prices with drug companies, it is interesting to note how this sector’s performance has been underwhelming since the end of March.

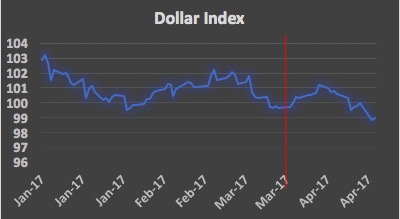

It is finally worth looking at different gauges, like the dollar index, measuring the greenback’s strength against other major currencies, and gold, the go-to-asset in volatile and uncertain periods par excellence. The former index showed a marked move down in the days surrounding (especially preceding, as problems emerged) March 24, indicating how investors became nervous about Mr. Trump’s presidential promises, and then later recovered part of its losses as the US economy proved to be still strong in terms of unemployment and payroll numbers, which increased according the latest round of economic data. The latter measure finally appears to indicate a sentiment of risk aversion and uncertainty among market operators that has been growing since the beginning of 2017, probably mainly due to general macro-political events, even though a spike right before the AHCA vote is clearly notable as well, and could again be possibly interpreted as a sign of nervousness.

Sources and References: Nasdaq, Bloomberg, Reuters, Zephyr, Financial Times, Companies’ annual reports and websites, Wall Street Journal, Marketwatch, Standard and Poor’s

To contact the authors:

Federico Cattani federico.cattani@studbocconi.it

Marco Monaco marco.monaco@studbocconi.it

Elisa Forghieri elisa.forghieri@studbocconi.it

Adele Bertolino adele.bertolino@studbocconi.it

Umberto Armani umberto.armani@studbocconi.it

Camilla Veroni camilla.veroni@studbocconi.it

You must be logged in to post a comment.